Sex doesn't sell, it's fear. In the first episode of Mad Men (Smoke gets in your eyes) Don Draper outlines the appeal of fear as a tool for selling with chilling clarity. "Advertising is based on one thing: happiness," he calmly tells his clients. "And do you know what happiness is? … It's freedom from fear."

This has been the simple quest of consumerism for the past half-century: to pinpoint with laser-like accuracy the anxieties of the consumer at any given moment, from the nebulous (economic insecurity) to the specific (bird flu). One former marketing executive from a soft drinks multinational even told me how they would brainstorm these anxieties on a "whiteboard of worry". The purpose? To brilliantly, cunningly hone a product that offers temporary "freedom from fear", temporary because a new fear and a new product will be on their way soon. Here are some of the ways it is done.

How 9/11 sold us the Hummer – as a suburban car

After the September 11 attacks, market research suggested the public were now terrified of "the outside", generally, and an opportunity was spotted by an extraordinary French anthropologist called Clotaire Rapaille, who lives in a big, spooky chateau. For more than 30 years, he's been advising companies such as General Motors, Kellogg's and Philip Morris on how to exploit what he calls, scarily, the consumer's "reptilian brain". This reptilian brain could be triggered to sell cars, and Rapaille believed a military vehicle designed for war could now be sold to bankers in golfing jumpers. Yes, the Hummer was coming to Clapham. "It's a weapon," he told me. "The message is: 'Don't mess with me. If you want to bump into me I'm going to crush you and I'm going to kill you.'"

With people fearful of the outside world, the car now needed to offer sanctuary. "It gives me superiority in a very dangerous world," Rapaille says. The aggressive Humvee mindset spawned a less antisocial alternative: the SUV (sport utility vehicle), with its high-up military-style vantage point, from which to spot approaching danger, and with macho bumpers signalling solidity and indestructibility. Even the cup holders, says Rapaille, are not really about holding cups: they reinforce a psychological signal of stability. SUV sales soared and in the early noughties accounted for more than 20% of all American car sales.

In reality, SUVs were the opposite of the message they sent out: far more likely to roll over than smaller, lower cars. But the illusion of safety is what mattered. Freedom from fear, even if that freedom is a chimera, sells the thing to us.

Where it all began: bad breath

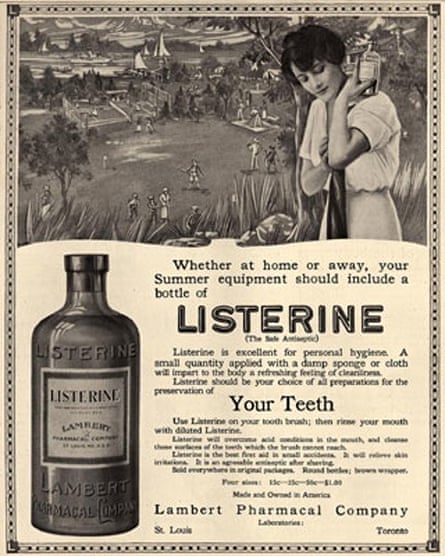

"Jane has a pretty face. Men notice her lovely figure but never linger long. Because Jane has one big minus on her report card – halitosis: bad breath." (1950s advertisement for Listerine.)

Stanley B Resor took over the advertising agency J Walter Thompson in 1916 with a vision of humanity, as a writhing mass, jostling for food and safety, but united by one thing: fear, according to marketing expert Joel Sachs. Resor wanted to utilise the latest developments in European psychoanalysis (Freud) and believed constructing fear and then providing the product solution was the key to modern consumerism. So, when the producers of an obscure antiseptic called Listerine were looking for a new market, Resor had the answer.

Listerine was going to be the cure for an international epidemic of unimaginable proportions. What could this terrible disease be? It had a medical name and everything: it was halitosis and we've been gargling ever since.

How bird flu sold soap

There's virtually no difference between conventional soap and antibacterial soap. The traditional bar, which hasn't changed since the 1940s, kills almost as many germs as the antibacterial. But we don't believe that – and we have bird flu and Sars to thank. Before selling soap through fear of germs, it was sold as a luxury: Imperial Leather and the soap-suddy pleasure of the long bath taken by the blonde woman on a break from the Flake ad.

But antibacterial soaps changed all that: hygiene was the new war zone and the genius of the idea was to convince us that every domestic surface was teeming with salmonella, E coli and baby-threatening diseases of every kind, and so requiring manic spraying every 15 seconds. Soap went from the bathroom to the kitchen, and OCD had an unwitting enabler.

Barry Shafe, Cussons' former head of product development and the man behind Carex's launch in the UK, tells me the background noise of pandemic fear was all that was needed to drive consumers to antibacterial soap. They didn't need to ramp up the fear with advertising because real fear sells far better than invented fear. But it also helps if your soap is blue (medical-looking) and comes in a squirty, transparent square bottle (square and transparent equals, wait for it, honesty).

Jumping the shark: the Brickhouse Child Locator

Here is one you would think would never get past the Dragons' Den pitching stage, but it did. "Every parent's worst nightmare," begins the advert. A mum is darting frantically around the children's playground searching for her missing son. Paedomania is rife. But thank God! He is wearing an electronic tag, a Brickhouse Child Locator, to be precise. Some fear-stoking simply goes too far: we don't mind being scared (we actually enjoy the experience of a rollercoaster ride) but child abduction, no thanks. The kiddie tag never took off, thank heavens – the batteries alone would have cost a fortune.

The damsel in distress and the hero product

Everything from kitchen roll to chocolate bars has been cast in the role of hero, riding in to save the day and banish the fear. We are too knowing nowadays to buy the six-pack chiselled hero so the hero is now invariably semi-comic or ironic (the You're So Money Supermarket Dad, and the Juan Sheet kitchen roll Zorro).

Because the damsel in distress is the consumer, we can now be rescued from absolutely anything: roadside breakdown heroes rescue women (important that it is a woman) on dimly lit backstreets, sure, but beer can also come to the rescue of thirst, washing powder to the rescue of parents, gravy granules to the rescue of Sunday lunch. It is ridiculous but we fall for it.

'Consumers remember basically one thing and one thing only" – so make sure that thing is scary'

Bob Ehrlich helped launch the bestselling drug of all time: lipitor, a powerful statin used to treat high cholesterol. The reality of heart disease and stroke is that they have multiple, complex causes, but many of us believe cholesterol is the only one that counts.

So how did cholesterol get the rap? Because the drugs industry had developed drugs … that lowered cholesterol. And boy, they needed to sell them somehow.

"It's an interesting problem we had, which was we couldn't say lipitor prevents heart attacks," says Ehrlich. "So we decided to focus on what we could focus on, which was we're the best at lowering cholesterol. And we went out and advertised that."

A committee of the National Institutes of Health in the US subsequently lowered the threshold at which cholesterol was considered too high. Six of the seven committee doctors who made that key decision had financial ties to Pfizer – who made lipitor.

Of course, fear of risk is actually the bestselling tool of all: it is the basis of the entire insurance industry, whose profit base is predicated on the fact that fear is a very real emotion selling the product, but the statistical probability of anything actually happening, well, that is infinitesimal. Fear through risk sells us a product we don't even use. Genius.

Vitamin Water can cure cancer

Rohan Oza went to Harrow School, but can now be found residing in his luxury hillside penthouse overlooking Los Angeles, thanks to the product that distills fear marketing into a single bottle of sugary water. It made Oza and his business partner, rapper 50 Cent, a lot of money. How much? "It's a new agreement we have. I don't tell people how much money he made and he doesn't shoot me," he says.

When Coke bought Vitamin Water, in 2007, says lawyer Stephen Gardner, extraordinary health claims were made. "It would inhibit growth of tumours, which is double-talk for prevent cancer, of the skin, lung, oral cavity, oesophagus, stomach, liver, prostate and other organs," he says. "Awesome. But not true."

Coke dialled down the health claims but in 2009, the Advertising Standards Authority said it couldn't even be considered "healthy" because a bottle had almost as much sugar as a can of coke. Vitamin Water had been sold to alleviate fear, but now ended up justifying it.

Fear of missing out

Not all fear-selling is about the horrors of bad breath and a potential terrorist attack. Some – indeed the most effective campaigns – target the plain old fear of missing out. Fear of missing out drives the upgrade culture around smartphones and technology but even applies to embracing danger. New technology (recording and posting your thrilling life – snowboarding, Rio carnival, bungee jumping) and adventure holidays that service these thrills, are about ticking off the bucket list before you are 21. Why? Because if you haven't looked fear in the face and enjoyed it, you haven't lived.

Jacques Peretti's series The Men Who Made Us Spend is on BBC2 on Saturday. You can watch all three episodes in the series on the BBC iPlayer

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion